A potted history

From The Jersey Tourism website

The presence of oyster shells at La Hougue Bie, a Neolithic passage grave constructed between 2,000 and 4,000 years ago provide evidence of early fishing in Jersey.

After this time documented evidence does not exist until the 13th Century, when a large salt and wine trade existed between the Continent and Britain. The Channel Islands were important in this trade given the location and the added benefit of not having to pay British duty. Indeed Jersey boats, under concessions to the British King, were able to buy salt from Cadiz at more favourable rates than French boats.

The fishing industry seems to have been closely connected with these trades as ships returning empty from Britain often loaded with salted and dried fish from the Islands for sale in Catholic Countries where a fish diet was obligatory on certain days and seasons. The value of this latter trade must have been considerable because in 1247 strict regulations were enforced covering the period from Easter to Michaelmas to enable the King to collect duties from the 'eperqueries' or conger drying places. During the rest of the years congers were sold in the same way as any other fish.

In 1332 a report by Dupont to the King's Justices showed that approximately a quarter of customs revenue was taken from fisheries, and over a third was derived from all marine activities. The first mention of exploitation of the Gorey oyster beds is made in 1445, but it is most doubtful that this was on the same scale as 400 years later.

George Balleine in his paper about 17th century social life states that “almost every farmer had his boat and went fishing occasionally; but there were also whole-time fishermen, for loaves and fishes, especially congers, were still the staple food of the island. The sea about these islands may be called the kingdom of congers….”

The cod fishery

The development of the Newfoundland cod fishery had a profound effect on the fishing industry. Newfoundland had been discovered by Cabot in 1497 (legend claimed a Mr Munn of Jersey discovered it 50 years before) and initially it is thought Jerseymen signed on with French vessels. However, in 1581 it was estimated that 17 vessels left St Helier for Newfoundland.

Dumaresq, in his survey of Jersey in 1685, states that “the most able-bodied young men with any ambition took to seafaring, many going to Newfoundland between spring and autumn and earning up to £20, while in the winter they earned about £3 on the farms."

In 1763 the Gaspe Peninsula was ceded to Britain by the Treaty of Paris, and in 1767 Charles Robin sailed to the area and established a fishery under the auspices of Robin, Pipon and Co. At its height the company employed 4,000 men and in 1845 gave employment to 8,000 of Jersey’s 27,000 tons of shipping. The fish taken were sold as far away as Brazil and Naples and, after the Hudson Bay Co, this Jersey company was regarded as “the best syndicated business in North America directed to a single definite end”.

The fish were caught by seines and lines using dories. The fish were dried, salted and dispatched in wooden tubs, each holding 112lb, and shipped to various markets around the world. Although the company collapsed following the advent of iron clad ships in around 1886, dried cod from Newfoundland was still a feature of Jersey trade into the early 20th Century.

- Jersey's involvement in the Newfoundland and Gaspe cod fishing industry

- Charles Robin, and the history of Jersey's fishing industry off the Canadian Atlantic coast

- A history of the Fruing family and its Canadian business

- 18th century trade, an article from the 1981 Annual Bulletin of La Société Jersiaise

- Emigrants from Jersey, the cod, and the Gaspé Coast, by George F Le Feuvre

- Jersey Settlements in Gaspé, by Marguerite Syvret

- Plying to the Gaspé Coast by A J Romeril

- Everyday life on the coast of Acadia. by Marguerite Syvret

- The Origins of the Béchervaise Family in Gaspé

- A brief history of the Gaspé Peninsula

- Percé Rock

- Charles Robin, a forgotten Father of Canada

- Emigrants to Canada, a full alphabetical index to emigrants to Gaspé, Newfoundland etc

- Trachy family in Gaspé

The oyster fishery

The oyster fishery which flourished in Jersey during the last century was probably the most successful indigenous fishery in the Island’s history. At its height it employed 2,000 fishermen working 300 smacks from 1 September to 1 June, as well as providing work for about 1,000 of the poorer inhabitants of the east coast of the Island.

In 1797 several oyster banks were discovered by British and Jersey fishermen a few miles to the north west of the Iles de Chaussey, between three and nine miles from the French coast. The distraction of the Revolution prevented the French from exploiting the beds and the Jersey fishermen took full advantage and developed the fishery.

In 1810 a regular export was established to supply the Kent and Sussex oyster companies. The port of Gorey was used to transfer the catch to English vessels. By 1830 the Kent and Sussex firms employed upwards of 250 boats each with a crew of six. A further 70 boats from other ports including Portsmouth, Southampton and Shoreham also worked the bed. The trade brought as much as £40,000 a year into Jersey and to meet the growing needs of the industry, port facilities were improved. A pier was built at Gorey and jetties were constructed at BouleyBay, Rozel and La Rocque. There was also a pickling factory at Gorey.

By 1833 the fishery was concentrated on the beds in GrouvilleBay. This had come about due to the successful opposition by the French to the dredging of the beds off Chassey by English vessels. In 1821 a French armed vessel had harassed the dredgers and in May 1822 a commission was formed to survey the disputed grounds. A naval vessel was sent to protect boats fishing more than three miles from the French coast. In 1824 this was increased to six miles effectively excluding Jersey and English vessels from the banks and forcing them to fish in Grouville Bay. These banks were incapable of sustaining such pressure and the effects of overfishing became apparent. In 1835 only 150,000 bushels were dredged compared with 306,000 the previous year. After 1862 many of the English vessels had left the Island to fish the beds off Dieppe, and by 1871 only six oyster boats were left.

Fishing gradually became inshore and short range with Les Ecrehous and Les Minquiers being the main offshore areas fished. In the early part of the 20th Century boats usually sailed out to these reefs and stayed there all week potting. The fishing industry was hit hard by the 1914 - 1918 War and did not really recover during the inter-war period with only a handful of full time fishermen operating. During WWII fishing almost ceased. Licences were granted but fishing areas were severely restricted because of the minefields.

After the war, fishing for lobster formed the major activity for the fleet which increased steadily from six vessels in the late 1940s to 15 full-time in the late 1960s.

Inshore and low-water fishing

Jerseymen have long fished the waters in the immediate vicinity of their island. In early times, fishing for many was a way of life. The men who risked their lives in small vessels off Jersey's rocky coastline were initially not interested in selling their catch, merely in finding food for their families and the small communities they were part of.

Some would have used nothing larger than a home-made dinghy and would have fished in sheltered bays. Those who were successful may have been able to acquire a larger boat and venture a little further afield, perhaps catching sufficient fish to be able to sell them - after the Rector had been given the tithe to which he was entitled.

20th century

From the Jersey Harbours website By Don Thompson, President of the Jersey Fishing Federation

Cod and oysters

Jersey’s historic fishing industry dates back to the 1800s and the great pioneers who crossed the Atlantic under sail to catch cod and to eventually establish a Jersey community on the Gaspé Peninsula.

Closer to home during the 1800s, we also had a big fleet of sailing trawlers fishing oysters to the east of Jersey. With a big French fleet targeting the same stocks, there was much angry conflict and seizure of boats on each side was a common occurrence. The offshoot of the conflict was the 1839 Bay of Granville Agreement, known to be the first international fisheries agreement ever negotiated.

In the early 1950s Jersey fishermen pioneered the Channel fishery for crab, using offshore vivier boats previously unknown outside of Brittany. Those boats went on to exploit new grounds as far north as West Scotland and the Hebrides.

Jersey merchants, with the plentiful landings of crab and lobster were able to influence European prices and help keep the island on the map. Back then the fleet used to lay up along the wall, on the mud where the St Helier marina is now sited.

The fleet then moved to the end of the New North and on to the South Pier in the 60s. It was a fantastic sight to see the fleet tied two and three abreast for the full length of the quay on a spring tide.

Association

The Jersey Fishermen’s Association was established in 1955. The association to this day represents the professional fleet on the local and international stage.

Some fishermen successfully moved to the trawl and beam trawl sector and often exploited grounds in the Western Approaches far from home. Access to EU funds, new bigger boats, increasing layers of regulation and development of new fisheries elsewhere has seen the demise of both our vivier boats and bigger trawlers.

Survey

Gallery

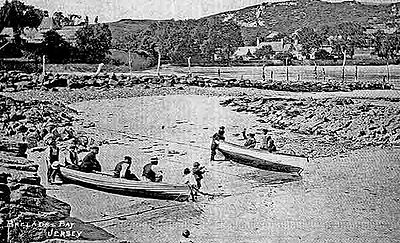

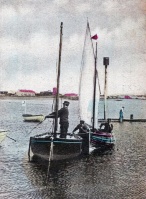

Fishing boats in St Helier Harbour in 1880

Razor fishing at Havre des Pas in the 1930s. Razor fish are buried under the surface of the sand. Dropping a pinch of salt down the hole at low tide brings them to the surface

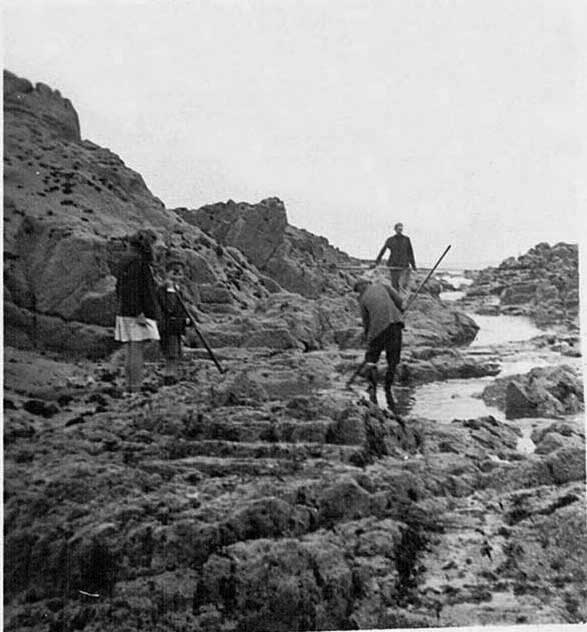

Rock pool fishing at La Corbiere

A good catch at Portelet in 1908

Fishing boats at Havre des Pas

Sand eeling below Mont Orgueil in the late 1940s

Lobster pots on the quayside at St Helier Harbour