Confiscation of wireless sets

The ban and subsequent confiscation of the civilian population's wireless sets in June 1942 was one of the most controversial measures imposed by the German authorities and represented a major intervention in island life. It triggered defiance on a massive scale and is of vital interest to our story, as some of its protagonists fell victim to German action taken against the continued reception of BBC news. Probably the best remembered of the 'wireless cases' in occupied Jersey occurred in the parish of St Saviour in spring 1943. It involved - among many others - four of the people whose names are engraved on the Jersey memorial: Canon Clifford Cohu, John Whitley Nicolle, Joseph Tierney and Arthur Dimery.

Canon Cohu

Clifford John Cohu was born in Câtel, Guernsey on December 30, 1883 as the son of Reverend Jean Rougier Cohu and Ada Sophia Orange. In 1884 the family moved to Yorkshire where his father was the Headmaster of Richmond Grammar School until 1890. Thereafter the Cohus lived at Aston Clinton in Buckinghamshire.

Educated at Elizabeth College, Guernsey and Keble College, Oxford, Cohu was ordained priest in 1908. In 1912 he went to India where he served as a minister in several communities, including as Canon of Allahabad Cathedral, until 1935. He was highly regarded for his straightforwardness and chivalry, earning the affectionate designation of pukka sahib from the local populace. He was a member of the Indian Ecclesiastical Establishment in Lucknow and held the rank of Colonel in the chaplain's department on his decommission in October 1935.

He retired to Jersey in 1937 where he lived at Holly Lodge, Five Oaks with his wife Harriet, whom he had met in India. He was assigned as acting rector of St Saviour when the post became vacant in 1940. Despite his eccentricity, Cohu enjoyed wide-spread popularity and, consequently, became the single most prominent member of the island community to have died in a German camp.

Twenty-three years in India had a profound influence on this highly sensitive man, something that found more than an adequate expression in the obituary which appeared in the Evening Post on 29 September 1945. The author, a friend of the Canon, bears testimony to a man who 'persistently refused to be caught by the cheap simplicity of a logic which ignores half of human nature'.

And further: ‘He would not purchase emphasis at the cost of ignoring obvious facts. If life is many-sided, as it certainly is, then faith which is one-sided stands convicted of inadequacy: he knew that the solution of a complicated problem cannot but be complicated itself.’

Many islanders still fondly cherish his memory and remember his acts of defiance, most spectacularly his rendering of the news while riding down the Parade, St Helier on his bicycle on at least one occasion. In his position as chaplain of the General Hospital he further challenged German authority by disseminating information on his visits to the general and maternity wards.

Joseph Tierney

Cohu's source of information was the parish cemetery worker Joseph Tierney who wrote out the news he received every morning from John Whitley Nicolle and his father, a St Saviour farmer, who retained a radio set which had been loaned to them by Mrs Bathe. On the basis of this information news sheets were produced by Tierney and Arthur Wakeham, which were then carried to Canon Cohu and Henry Coutanche who worked at St Saviour's Parish Hall.6 While the threat to the Germans from such behaviour was little more than innocuous, Cohu’s non-conformism made him a thorn in the Germans’ side and catapulted him to the top of the occupier’s blacklist of ‘undesirables’.

Substantiating this is a letter Harriet Cohu wrote to the Attorney General after the Occupation and in which she pointed out that her husband's arrest had entailed no house-searches and no questioning of herself nor of the companion who was living with them, Miss Eleanor Margaret Curtis, but that his 'chief fault in their eyes [the Germans'] was that he tried to keep up other people's spirits.'

Joseph Tierney, who was living at 23 Cheapside in St Helier, was the first member of the network to be seized, on March 3, 1943, followed by a number of arrests over the ensuing fortnight. Cohu himself was arrested by the GFP, the German Secret Field Police, and taken to their HQ at Silvertide, Havre des Pas, in a car on Friday, March 12.

Surviving documents show that in the end a total of eighteen people were tried - most of them for receiving and disseminating BBC news or assisting this endeavour in one way or the other. However, it appears that the number of people interrogated was higher. Law draftsman Francis de Lisle Bois passed a warning from Cohu to Reverend Matthew Le Marinel, the rector of St Helier, and Curate Preston who were equally involved in the spreading of news.

With so many people involved, most of whom had probably never prepared for the eventuality of being arrested, there was plenty of scope for manoeuvre and a gifted interrogator would have had few problems trying to retrieve the type of information needed to indict as many people as possible.

The German authorities were becoming increasingly nervous about popular disobedience to the wireless confiscation order, a measure the FK had never been enthusiastic about it, owing to the difficulty of its enforcement and the potential it carried for undermining its own authority. A purportedly harmless activity, when banned, turned overnight into an act of great significance.

The continued reception of news now represented an act of defiance which challenged the FK's total authority. Once tarnished, a loss of authority could easily extend into other areas. A go-soft approach to this issue was therefore out of the question.

Show trial

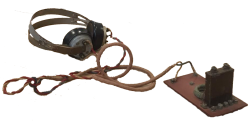

The St Saviour's wireless case was the perfect opportunity to stage a show-trial that could act as a deterrent and persuade the rest of the population to refrain from illegal action. However, the result was forcefully counter-productive, with the challenge to the FK’s supremacy spreading into other areas: though islanders became more circumspect, they also became more technically ingenious and developed all kinds of virtually undetectable crystal sets.

As is attested in many diaries and memoirs, news invariably found its way around the Island. Having handed in one set, many people kept a replica hidden away in a safe place and an impressive number of these contraptions appeared on window-sills on 8 May 1945, ready to blast out Churchill’s speech.

The trial took place, barely one month after the arrests, on April 9, 1943, behind closed doors in the Lower Committee Room of the States Building. Eager to give this one occasion a semblance of legality and exploit it for propaganda purposes, the court made a unique provision for Advocate Valpy, Mrs Bathe's lawyer, to act as defence counsel.

This is the only documented case where an Island lawyer was ever allowed to defend a client in a German court. Not that it made any difference; as in Valpy's view the outcome of the trial was clear from the outset; the court procedures bore no resemblance to the standards required in a fair trial; guilt was assumed and all the defence counsel could do was plead in mitigation.

However, unlike other trials, the case enjoyed a great deal of public exposure - something the Germans surely could have avoided had they aimed for more secrecy. Donald Journeaux, one of the defendants, recounts that on leaving the States Building after the trial, large crowds had gathered in the Royal Square, eagerly awaiting the result - a fact substantiated by an entry in Sinel's Occupation diary.

A determination to rid the Island of Cohu's presence forever accounts for the disproportionately harsh sentence he received, in striking contrast to the sentences given to other defendants for very much the same offence. Cohu was sentenced to 18 months imprisonment for 'failing to surrender leaflets and disseminating anti- German news', whereas usually sentences for convictions of this category ranged between a mere one to two months. Equally, Tierney's two-year sentence 'for manufacturing and distributing leaflets' appears as a telling idiosyncrasy in the light of the two months imposed on another defendant, Arthur Stanley Wakeham, for an identical offence. Clearly a hidden agenda was at work seeking to isolate 'troublemakers' and emblematic figures like Cohu.

'Chief criminal'

The second blow was directed at those believed to demonstrate initiative, as shown in the case of Tierney and Nicolle (the latter being branded as the chief 'criminal' by the German prosecution)

The third line of attack targeted those involved who were English-born, as in the case of Arthur Dimery. He was a gardener whose crime constituted having dug up Mrs Bathe's wireless set which, afterwards, was handed over to Mr Nicolle. Dimery's relatively low sentence of three months and two weeks was to be served on the Continent, from where he never returned.

He left Jersey for an unknown destination together with Nicolle, on5 May 1943. After completing his term he probably found himself in the hands of the Gestapo and was sent to Neuengamme concentration camp, outside Hamburg.

How Dimery came to be admitted to Laufen, one of the internment camps for Channel Islanders, remains a mystery. He died there on 4 April 1944 and lies buried at Salzach Municipal Cemetery.

Five days after the verdict, on April 14, 1943, Cohu was transferred from the military (German) to the civilian side of Gloucester Street prison where life was relatively easier. The Germans had taken over two blocks of the prison for their own purposes. The larger building was reserved for German servicemen and the smaller for civilian 'offenders' against the occupying authority. The civilians remained in the German part of the prison until the time of their trial; however, once the German court had reached a verdict, prisoners were transferred to the ‘civilian side’ under the Jersey authorities.

Cohu spent three months in the civilian side before being shipped to the Continent on July 13. His first way-station was Fort d'Hauteville, near Dijon.

Tierney, who in the meantime had been allowed to attend the christening ceremony of his new-born daughter, followed him there on September 18, 1943. The relocation of prisoners to Dijon was necessitated by the pressures of accommodating a growing torrent of prisoners at the French central prison of Villeneuve St Georges. Henceforth the Fort of Hauteville started to share the functions of the central prison and became a collecting point for all those selected to serve their sentences in Germany.

Five of the ‘Frankfurt and Naumburg Seven’ were regrouped at Hauteville: Canon Cohu, Joseph Tierney, Frederick Page, Clifford Querée and George Fox. All ended up together at Saarbrücken prison in Germany on December 21, 1943.

They were transferred to the prison of Frankfurt-Preungesheim on January 6, 1944. Nicolle, who had also joined the other prisoners at Hauteville left Saarbrücken with Alfred Connor, a Jerseyman arrested for possession of explosives in 194317, for an altogether different destination. Both men were transferred to Zweibrücken on December 27, 1943, where they were retained for a few months and then sent to Bochum where they arrived on April 17, 1944.

The fact that Nicolle had been sentenced to three years simple prison and that prison terms over two years were executed at Bochum prison accounted for his separation from the other prisoners. However, Nicolle was then sent on to Dortmund where he arrived on April 21. This prison was particularly vile as is recounted by one survivor, according to whom Bochum was 'bad, but it was a palace compared to Dortmund'. John Nicolle perished there from starvation and overwork.