Organisation Todt

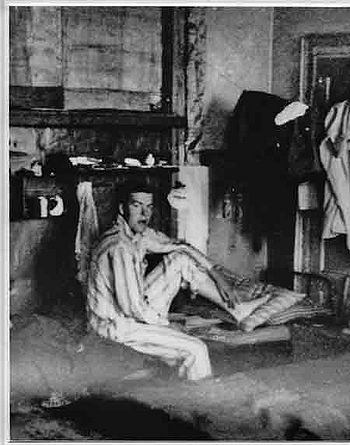

Forced workers had meagre rations, threadbare clothing and suffered enormous deprivation at the hands of their German masters. Most worked for the notorious Organisation Todt, a civil and military engineering group named after its founder, Fritz Todt, an engineer and senior Nazi figure. The organization was responsible for a huge range of engineering projects both in pre-World War II Germany, and in Germany itself and occupied territories from the Channel Islands to the Soviet Union during the war, and became notorious for using forced labour.

The Organisation Todt workers were not strictly ‘slave workers’ as they are frequently described, because some were actually volunteers. Most were forcibly recruited, but were paid and not generally ill-treated. The real slave workers were citizens of the Soviet Union, mostly from the Ukraine. The Nazi philosophy was that the Germans were the master race. They treated other Europeans with contempt and believed that the Slav races who were ‘untermenschen’ (sub-human).

The conscripted work force was made up of political dissidents from various parts of Europe, in particular Holland plus many hundreds of Spaniards who had fought on the Republican side in the Spanish Civil War of 1936-39 and then had taken refuge in France. They were virtually handed over as a gift to the Organisation Todt by the collaborationist French Vichy government.

- A more detailed article on Organisation Todt Added 2016

Helper's recollections

This description of the life of forced workers in Jersey was written by someone who was involved in helping them during the Occupation and is taken from a Jersey Heritage factsheet.

- "The first foreign recruited labour began to arrive in 1941 working in fortifications at Noirmont. The real waves came in the summer of 1942 with the peak of building activity being in 1943. Early in 1944 the majority were moved to other defensive works in France but some were in Jersey until the end. These were all returned to their own countries by August 1945 except for a handful of Dutch and Spaniards who had been given permission to many local girls.

- "All except the Russians were paid in Reichmarks which was a currency valid only in occupied territories, not even valid in Germany itself where the national currency, the Deutschmark was used. They had reasonable, if cramped, living conditions in camps and were free to leave their camps outside of working hours.

- "The treatment of the Russians, on the contrary, was truly terrible. On paper, their rations were adequate, something doubtlessly worked out by a nutritionist in the Food Ministry in Berlin as being the minimum necessary to get a day’s work out of a young man. This food would certainly have been withdrawn from stores but did not reach the bowls of the ‘sub-human’ Russians. It was progressively siphoned off by O.T employees and guards at all points, from source to the camp kitchens, for sale on the black market.

- "Not surprisingly, many of the prisoners attempted to escape. But where? It was not that difficult to get out of a camp at night but there was no hope of being able to cross the sea to France, leave alone to England. There were frequent warning to civilians of the penalties for aiding these workers in any way, even of giving them food. Most were civilians, in some cases boys as young as fifteen picked up in the street on their way home from school but others had been in the armed services, were prisoners of war.

- "In spite of the warnings a large number of Jersey people did help them, some with no more than a meal, but many took them into their homes, kitted them out with clothes, gave them hospitality, a bed. This was highly dangerous and more so in rural areas were a stranger going in and out of a house was more likely to be noticed than in a flat in a block in the town where life is impersonal. It was wiser to move a man on after a few weeks before neighbours began to talk.

- "Although only about 25 such escapees emerged from the woodwork on Liberation Day, most of them had had several homes so that several hundred Jersey people must have been involved in hiding them. Even sixty years after the events the writer if frequently amazed to hear that this friend or that had uncles and aunts who had a Russian prisoner for a month or so. One is even rumoured to have played one winter in the St Martin’s Parish football team.

- "The penalty for being discovered was several months in prison or even worse. One such prisoner was a St Ouen’s widow, a Mrs Louisa Gould, whose prison sentence had to be served on the Continent. This was in 1944 when the Allies were already in Normandy. She was moved east into Germany, finished up in the notorious concentration camp at Ravensbrück where, unable to keep up the workload and suffering from oedema, she was sent to the gas chamber in January 1945. Her brother, Harold le Druillenec, was the only British living inmate when Belsen was liberated in April of that year.

- "At the time, of course, names of those involved in hiding prisoners were never disclosed. The compiler of these notes did not personally hide any Russian escapees but sought homes for those needing to be moved. Only Christian names of those involved were used and even those were false ones. This meant that no list existed at the time. It should have been compiled later but was not thought of until, by then, it was too late because those who know had died.

- "The motivation by some was solely a means to defiance of the Germans, by a small number Communist sympathy but for most it was common humanity, an overwhelming need to try and help victims of brutality. It was more than one’s conscience could do to ignore it. To my knowledge, at least three prisoners were sheltered by conscientious objectors who would not have lifted a revolver to save their own lives or anyone else’s but were prepared to risk death to help someone in need. Would the congregation of the Ebenezer Methodist Chapel have guessed that the organ was being pumped by a young Russian escapee hidden behind the wooden screen? Would the Germans farm inspectors have guessed that the young lad at St John who showed them the stables speaking only Jersey-French, was another lad on the run?

- "Or would the Germans at the Havre des Pas pool who gave cigarettes to the Jerseyman who dived so spectacularly from the 30 foot board have realised that he was a Captain in the Soviet Army?

- "They were unusual times!

Numbers

German records show that in May 1943 there was a total of 16,000 foreign workers in Jersey, Guernsey and Alderney. In November 1943 numbers had fallen to 8,959 and by July 1944 only 817 remained.

Although no evidence of mass slaughter has been uncovered, there is a lot of evidence of sickening inhumanity by many against the slave workers. Beatings took place for the most trivial offences and in many cases the workers died.

Official indifference

It is only in very recent years that the true plight of the forced workers, particularly the Russians, has been officially recognised in Jersey and those who harboured and fed them have been honoured. An indication of what the island administration thought of the workers during the Occupation is given in a chapter of the diary published by the Bailiff's Secretary, Ralph Mollet, headed "A reign of terror".

- "On 13 August 1942 over one thousand arrived and were marched from St Helier to St Aubin - a very sorry sight - but on their departure in October 1943 they were in far better condition than when they arrived. From the day of their arrival they were constantly escaping from their camps in the country parishes. During the daytime they begged and robbed, and at night they attacked the houses in order to steal food and clothing. The local police were powerless."

It is difficult to know to what extent Mollet's comparative indifference to the prosecutions of islanders for harbouring forced workers and their transportation to the Continent reflects the views of the senior figures in Jersey's administration, but there is no doubt that for many years after the Occupation the foreigners, and particularly the Russians, were looked on as a problem and the network of islanders who tried to help them as an interfering nuisance. It was not until very late in the 20th century that these people began to be looked back on as heroes.

Stories of slave labour

The most numerous of slave workers were Russian prisoners, having been captured by the Nazis's during Hitler's invasion of Russia. Other nationalities included Jews, Poles, Belgians, French and Spanish Republican, many having fought against General Franco. A remarkable account of life as a Russian slave worker in Jersey was written by Vassily Marempolsky, who survived the most brutal treatment at the hands of the Germans

- Vassily Marempolsky's account

- A Jerseyman's memories of Russian forced workers

- Spanish Republican Juan Taule

- The story of a Spaniard who married a Jersey girl

- Information about islanders who helped and sheltered forced workers at great risk to themselves can be found in the Resistance article.

Westmount memorial

On 16 June 1960, a Russian timber ship arrived in Jersey. The crew were informed that many of their countrymen had been forced workers in the Island and with great interest were taken by coach to visit Westmount. Escorting them was Francis le Sueur and Norman Le Brocq, members of the Jersey Communist Party.

The crew of the SS Jarensk pooled their money and a plaque was made and inscribed in Russian, "Your motherland will never forget you."

Each year members of the Jersey Communist Party, the French community, Spanish Republicans who remained in Jersey after the Occupation, members of the Jewish community and a few years later a Russian Attache from the Embassy in London would lay flowers at this one plaque and remember all forced workers.

In 1975 the memorial that stands today was built with funds from the Public Health Committee and the plaques purchased by the nationalities concerned. The original Russian plaque was replaced with one commissioned by the Russian Embassy in London. The Jarensk plaque is now with the Jersey Heritage Trust.

Francisco Font, one of many who campaigned for the Memorial to be built, was the first Master of Ceremonies at Westmount. He was one of 1,500 Spanish Republicans used as forced labour building fortifications around the Island. Along with other Republicans he faced a nine month ordeal in the Island of Alderney where he witnessed atrocities and brutality in the extreme. After his death in 1981, the late Norman le Brocq and then Stella Perkins presided over the ceremony.

Forced workers' graves

Although there are undoubtedly hidden graves of forced workers throughout the island, those buried formally remained in the Strangers' Cemetery at Mont a l'Abbe until, in 1961, their remains were exhumed and removed to German Military Cemeteries.